Cloaked in shadow, a black man stands alone. Then, decidedly, he exposes himself with the flick of a lighter. The flame reflects off his eyelids as a gentle, youthful voice from East London seeps in:

They said I would inherit the earth one day so no one could know I was weak.

Because men like us don’t cry.

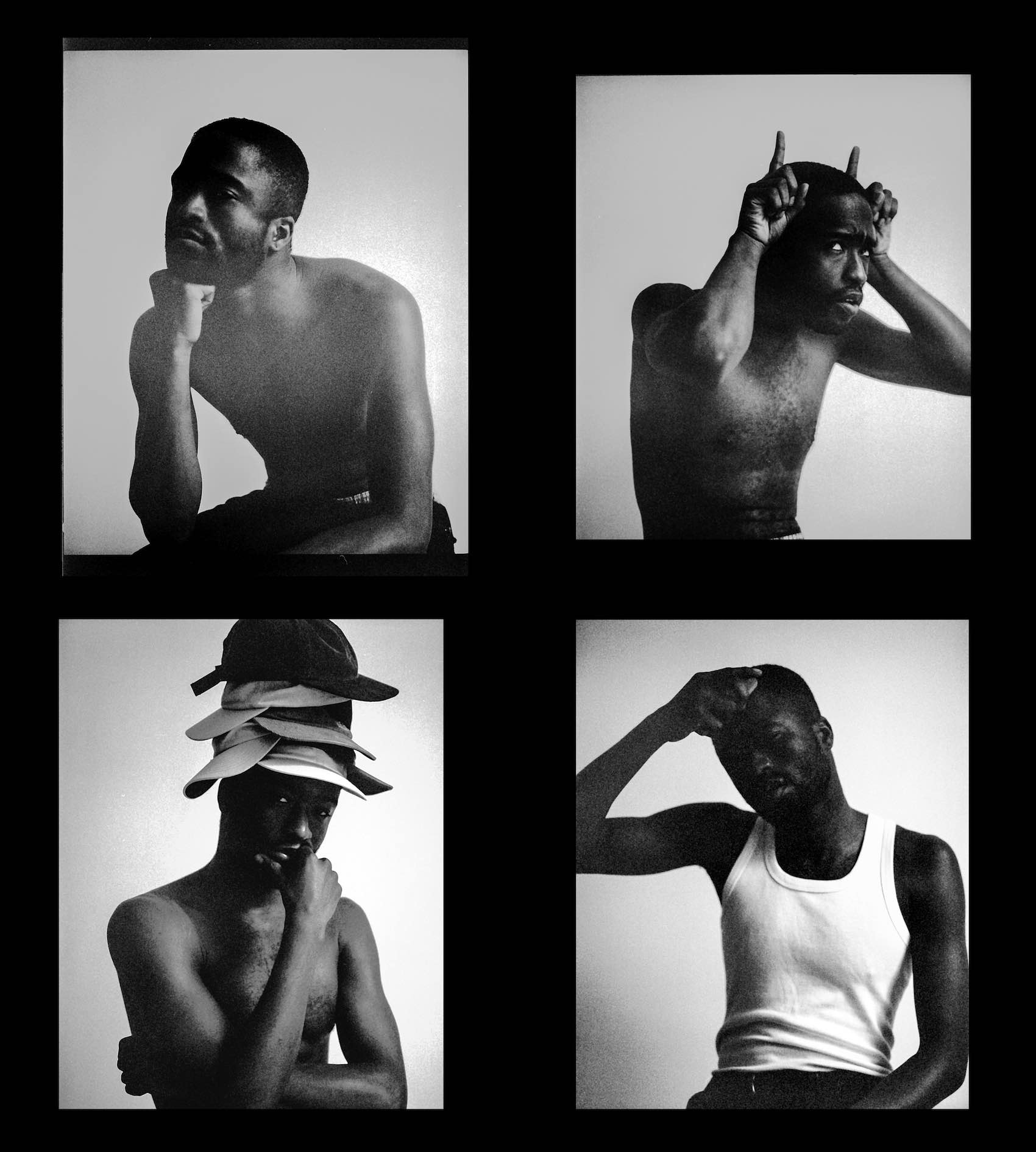

A group of young black men stand together, shirtless, with eyes closed and heads tilted upward. The camera stays fixed on the unmoored collective, and the voice speaks again:

So I tell you the story of the black boy who never cried.

He like I enslaved but no slave master in sight. Yet I am whipped until they see red meat. Stripped down from my head to my feet. Enslaved. No light. No savior. No sleep. Enslaved because we are too weak.

The voice belongs to the 23-year-old artist who goes by the name IggyLDN, reading from “Black Boys Don’t Cry,” his poem that equates emotional repression among black men to enslavement. He released an accompanying video with the poem in 2016, and though it has remained rather underground on YouTube since its debut, the fanfare it received was almost instantaneous. An interview with The Fader soon followed, as did a collaboration with Afropunk. The success of the poem and video is most notable for its brutal honesty. And also because the man behind it all was a novice.

“I never really followed poets or anything like that, but I think I was super gassed about loads of American poetry and how they were doing spoken-word battles,” Iggy says. “I always kind of envied everyone who could do poetry or write because I didn’t think I could write.”

An encouraging exchange with a friend during his time in college led to Iggy’s first public reading, where his thirst for expression was first quenched. The young artist prefers to keep his academic background and day job to himself, but he is willing to divulge that his creative pursuits are a stark departure from what he studied and now practices. Iggy is also more partial to the label of “creative director” than “poet,” and for good reason. He wrote, directed, and produced the video for “Black Boys Don’t Cry” as well as “Fatherhood,” a follow-up piece released last fall.

The “Fatherhood” video opens with a recorded exchange between Iggy and one of his brothers, who details his own emotional evolution. His brother admits that negativity has eclipsed sensitivity as he’s aged. His revelation is layered over a video of a black toddler playing on a bed before a backdrop of greenery. The poem meditates on quandaries like, “So how do you fix this shipwrecked history of dad meets son/Son becomes a man/Man becomes dad/Dad doesn’t act like dad anymore,” and echoes the refrain, “Mister Mister you seem to have neglected that we are born perfected in more ways than you projected.”

“I really wanted to showcase that in order to be a black man in the 21st century, it means you just need to be black and a man.”

While “Fatherhood” unpacks the stigmas of black masculinity, Iggy says his own father, with whom he still lives (along with his mother and two younger brothers), never stifled expression within the family. “I’ve always had that knowledge from him through experience that it’s okay to cry, it’s okay to be vulnerable, it’s okay to show your emotions,” Iggy says.

He points to a photo of himself as a toddler dressed in a girl’s coat to demonstrate the openness of his upbringing. “I’ve never seen myself trying to fit into a box in terms of sexuality. You need to be able to explore these things to understand them. When people try to exclude themselves from it, it’s almost as if they’re trying to exclude themselves from nature, from developing themselves or teaching themselves.”

Many counterpoints to antiquated stereotypes of black men have burst into the mainstream, and public reception indicates a promising transition on the horizon. Iggy cites Barry Jenkins, the Academy Award-winning director of Moonlight, as one of his creative role models for the layers of visibility afforded by the film.

“The reason why Moonlight is so important to me is because it shares the stories of people who have typically been silenced,”he says. “It was the constant representation of the young men who have always been silenced and seen as other. I would like to think that my work has the same authenticity.”

Iggy references artists like musician Steve Lacy and rapper Kevin Abstract, who is openly gay, as amplifiers of his message for men of color to do away with false expectations.

“I really wanted to showcase that in order to be a black man in the 21st century, it means you just need to be black and a man,” he says. “You don’t necessarily have to showcase yourself with a strong, aggressive manner. You can respond to the stimuli in your life, and you don’t have to conform or change for anyone or anyone else’s satisfaction.”

For artists with a message like Iggy’s, the time is now. He is keen on freeing the potential within young men who look like him, and his multi-platform approach is one he is confident will reach those he seeks to empower. Iggy plans to release a book that further elevates the image of young men of color within popular culture, with their own words outlined in a series of interviews as well as vignettes from Iggy.

“In the world of Instagram and hashtags, I feel like people have really been able to cultivate a certain amount of knowledge within themselves, to pioneer themselves,” he says with affection for those still coming of age. “However, I feel it’s important for me to showcase the unspoken narratives and be a voice for the younger generations. And to do it in a beautiful and profound way so that people stop and listen.”

His message is less a plea than a battle cry for the meek to not only inherit the earth, but to groom it into somewhere their sons will flourish. As Iggy writes in “Black Boys Don’t Cry,”

But why aren’t we taught to drop down our barriers and pick up our pens.

My fellow brothers we have a lot of work to do.