JEREMY O. HARRIS is late to meet me. An hour late. I don’t really mind, though— more time to sprawl out across the corner booth of Chinatown’s Dimes, where the mind behind Slave Play, Broadway’s biggest draw at the moment, has asked me to join him. We had landed on this place a few days before while walking out of his Suited shoot with Collier Schorr and had laughed at our own hipster banality in the decision. It’s Harris’ favorite restaurant, the 30-year-old admits to me, but it is a space that is quite aware of itself for being a “thing,” a hub for downtown New York’s elite who are presumably low waste and high style.

I’m banal too and order a matcha latte while waiting. When Harris arrives, he’s full of ideas. Lots and lots of ideas. One of them being: trying to pitch his good friend Harry Styles a few potential Saturday Night Live skits that would parody Slave Play. Styles was due to host the comedy show that week, and the ambiguously fluid former One Direction heartthrob may just be willing to do the playwright this solid. They had just hung out the day before: Styles accompanied Harris to a Sunday showing of Slave Play with a young woman who tweeted at the playwright that she was dying to see the show but couldn’t afford tickets.

Harris situates his 6-foot-4 frame in the booth, shrugs off his overcoat, and tosses his Telfar bag (a.k.a. “The Bushwick Birkin”) beside him, taking out his phone to read aloud the pitch ideas he had texted his fellow Gucci muse (Harris and Styles are both faces of the brand, and attended this year’s Met Ball on the arm of Gucci’s Alessandro Michele). Clearing his throat, he reveals there are three skit ideas: the first, a digital sketch that would focus on the stridently progressive and conspicuously wealthy students of Brooklyn’s Saint Ann’s School who are staging the first production of Slave Play, Jr. Harris muses that could be fun, especially if they cast croarticle-racially. Second idea: We meet an older Mid-western couple excited to tell their young son or daughter in an interracial couple all about a new play, — Play, word redacted because they’re too nervous to say the word “slave.” Or, lastly, an ad for a mood stabilizer for people of color who just saw Slave Play and now can’t stop screaming lines from the play at the white people in their lives.

I’m not really a fan of Styles, but I understand what a co-sign of his means for a show like Harris’. It’s a Broadway debut that titillates and exhausts the Great White Way and black Twitter alike, not only because it deals solely and squarely with the sexual and historical traumas that slavery wrought and continues to replay in our interracial entanglements today, but because its production makes him the youngest black male playwright to stage a play on Broadway. Since fast-tracking from its off-Broadway run at New York Theatre Workshop this past spring to Broadway’s Golden Theatre this fall, it has attracted the likes of Rihanna, whose song “Work” not only lies at the center of the production, but who also famously texted Harris throughout the evening during the play’s preview that she attended earlier this fall. Harris read those texts out loud a few weeks later to an all-black audience at the “blackout” Slave Play preview night. I, like most of the 800 black creatives that were assembled that evening—including Keke Palmer, Paloma Elsesser, Jesse Williams, and Kelela, howled in response to their exchange and the flouting of theater’s customs.

I tell Harris my money is on pitch number two. “Number two is gold. It’s classic SNL. This can be the landscape.” He nods in agreement. As he orders steak, I have to know how in his nascent career he has already become so good at ingratiating himself into the public conversation, the canon, the public eye with his first Broadway effort, after just having graduated from Yale Drama School in the spring. I mean, yes, we do live within the golden age of self-promotion, but Harris’ ascent is something else entirely.

How are Rihanna and Harry Styles texting a celebrity playwright casually? How is late-night host Seth Meyers being coaxed on-air and agreeing to purchase ten tickets to Harris’ show, while Harris sparkles and smirks in sequined custom Schiaparelli couture? How did he co-opt an entire hashtag, which previously had been dedicated to an online community that was fixated on racist kink, into now denoting a high art and popcultural phenomenon?

“I think it’s just the fact that no one was going to give me anything in the world easily and so in order to make sense of myself in certain spaces, I had to figure out the quickest way to move from the back of the room to the front,” he explains. “It’s like a scam, but it’s also a survival mechanism.”

I feel this deeply. Black folks have been making their own opportunities ad infinitum, dismantling systems that did not have us or our ascendence in mind. But as a black queer creative, there are consistent obstacles in place that widen the distance between where Harris is and where he wants to be.

Knowing the trajectory on which to send his work—his searing, beautiful, provocative, polarizing, nearly radioactive work—is vital. This knowledge is perhaps what propelled and fast-tracked Slave Play’s predecessor, Daddy, from the classrooms of Yale to New York’s Pershing Square Signature Center last spring, where it opened with Alan Cumming in the lead. Staged around a Bel Air infinity pool, Daddy centers on the imbalanced relationship between a black up-and-coming artist and his much older white sugar daddy and an impromptu visit from the black artist’s mother who is determined to save her son from this twisted romance.

Harris won the Paula Vogel Playwriting Award, Lorraine Hansberry Playwriting Award and Rosa Parks Playwriting Award, all in the same year. But I realize that for all his raw, award-winning talent and magnetizing personality, Harris is actually about the numbers. Throughout our conversation, he keeps score and makes mention of the odds often. The odds. The odds. The odds of him winning the Tony for “Best Play,” for example: “If your play isn’t still running in

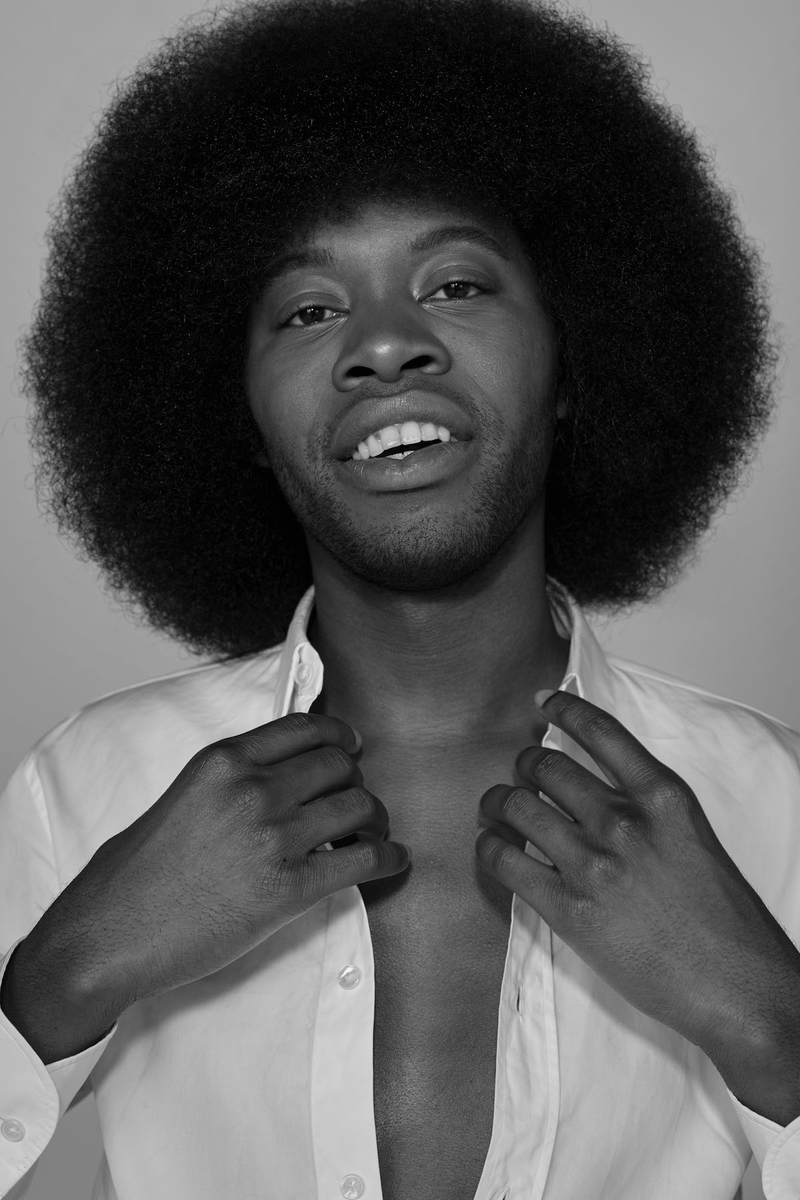

Jacket: The Row

In order to make sense of myself in certain spaces, i had to figure out the quickest way to move from the back of the room to the front.

June when the Tonys are happening, then statistically your chances of winning are zero,” he breathlessly explains. Slave Play’s run is only until January—for now. “And I think I’ve already given up hope that I was going to win because a black person hasn’t won since the year that I was born.” Harris points to the eight or nine shows that are within the nominating space this season, including Tracy Letts’starstudded production of The Minutes, and then the issue of real estate.

Drilling even deeper, he explains to me, “I think the thing that’s hard is that there is very little discourse in our community around what happens—even if your play is in the black, even if it’s doing really well—if you don’t want to be someone who’s making a 100 percent gross residual every week, because you realize 100 percent gross residual every week means most people can’t get in to see your play ... even if you are doing 95 percent occupancy every week and you are at the tip of the culture’s tongue, that doesn’t matter in the same way that dollars do. This is a commercial landscape.” But real estate aside, he muses, maybe his work doesn’t need a Tony, seeing as canonically it might be better for Slave Play’s legacy. Or, would a win signal to the black drama student who already feels erased within their theater program and the industry writ large, that there is a place for their work to be staged?

That Harris is preoccupied with the granular details of Tony nominations is understandable—any playwright would be—but I see it more as another example of how the chances were always stacked against him. He would have to defy them.

And he certainly has, first while growing up Martinsville, Virginia, where the whip-smart son of a beautician attended a tony private school that would be the bedrock of his education. The student body was predominantly white and wealthy. He was neither. But his family insisted upon him attending. They understood that his school would propel him past his station in life, the hurdles that growing up black and poor in the South would create.

This experience had a profound effect on how Harris began to privilege whiteness and how he viewed himself. As he wrote in a 2016 Vice personal essay, Harris bobbed and weaved through high school by impressing his peers with a vested interest in deep-cuts white culture; it distinguished him as a singular character, somewhat divorced from being defined solely by his race. He writes, “...[T]o find my way socially and academically, I became rich in white culture, while it, in turn, seemed to enrich me. I began to devour books, plays and movies to impress my peers, the more obscure the better. In doing so, I found that the world began to imbue me with the same weight and worth with which I had imbued white culture and bodies.”

I empathize with Harris. As any black kid who attends a PWI will tell you, there are survival mechanisms you initiate to pull you through. Because you are so often not immediately seen, you develop ways to challenge your erasure. That can play out in many different forms: acting out, acting up, performing one’s race for the white gaze, concealing it.

Later, at DePaul University, Harris eventually recognized how the vaunting of white male bodies and the subsequent devaluing of his own was colonizing his desires. He would work through this trauma in his writing, which we now see play out in Slave Play and Daddy. “Because I grew up poor and I was around rich people, I was the only poor kid in those spaces, and I feel my psyche learned to covet that sort of narrative around wealth and ascension and class—the heights of class—more so than the things about poor people, because there is no fabulation of poverty.” Really, I ask? Poverty is often aggrandized. “It’s just a fact in my life. I mean, there can be but it felt like too much of a fact to fabulate it. Whereas wealth, it all feels so bizarre and real and not possible. I mean, sfor me, wealth is an impossibility so, therefore, it’s more dramatic.”

Harris tells me of friends who will call him up to invite him to vacation on their family’s private island that was gifted from the English monarchy (“All of that sounds fake.”) or an ex who was traveling to Antarctica one holiday because it was the only continent he had never been to (“Like, how can you go to all the continents before you’re 80? Unless you’re an explorer!”).

True, it does make for good theater. This fabulation and fascination with wealth has his Slave Play protagonists venturing off to a sex therapy workshop for six days on a plantation, for one. But before Harris would reconcile these feelings in these works and be considered the new force behind American theater, the playwright would drop out of DePaul, after being unceremoniously cut from its acting program, and relocate to Los Angeles. Once there, he would go on to become a well-connected creative about town, who worked in high-end retail, toured with Florence and the Machine for 18 months, and eventually collaborated with one of the band members, Isabella Summers, on an off-off-Broadway play, Xander Xyst, Dragon 1. The recognition from that production would garner him a MacDowell Colony fellowship and push him to pursue his master’s degree. Using an early draft of Daddy as his admissions writing sample, Harris was accepted into Yale’s MFA program. He was back with theater, the love of his life.

“I need theater to be a part of the cultural conversation of my friends,” Harris tells me, as he bites into his steak. Thinking about the theater kid who hangs out with all the kids who turn up their noses at the idea of seeing a play on a Friday night, Slave Play is the happy medium, the playwright says. “I would tell my friends about some really cool show that I knew and they’d be like, ‘Ugh...a play?! Okay...’ I don’t want people to be dragging their feet to go see something that is the love of my life.” Harris grows emotional at that: He so clearly wants to share theater with others, especially those that look like him. It’s obvious, as he continues to talk to me about theater in a very authoritative way, an encyclopedic way, that he either assumes I know a lot about theater or that I should.

I don’t. The last play I saw before Slave Play was Eclipsed in 2016, with Lupita Nyong’o, and I was only able to attend because I was given comp tickets on assignment for Vogue. I admit this to Harris; he nods knowingly. “I never feel like it’s for me,” I say—despite Lorraine Hansberry, August Wilson, Suzan-Lori Parks, Danai Gurira, and so on.

I’m hardly the first black creative to acknowledge such a disconnect, which is why making his work accessible to the masses, rather than a rarefied few, is such a priority. He could have made Slave Play into an even bigger sensation, recasting it to include, say, Hugh Jackman or Laura Dern, or make ticket prices unattainable. But Slave Play and Daddy need to be seen by the people he intended. It’s why he’s staging another “black out” night of Slave Play in December —which he’ll most likely have to pay out of pocket again to facilitate. (In October, he and his producers all put up $5,000 to accommodate the evening.) “That’s the exciting thing about having [tickets for Slave Play] be $39 is that unlike a lot of other theatrical experiences that we know about and have never seen, and probably never will, I know the vast majority of people who are living in New York in 2019 got to see Slave Play because I made it accessible.”

They laugh with that laugh that’s like, ‘how could anyone say that?!’ but you thought it.

What’s interesting is that most of the criticism of Harris’ work derives from two camps: white theater critics who are offended by the renegade daring to be both a playwright and influencer, and #ados, or American Descendents of Slavery, an active community online who believe his writing undermines the atrocities of slavery for the entertainment of the white gaze.

There was the change.org petition to keep Slave Play off-Broadway, instigated by a theatergoer who described the production as the “most disrespectful displays of anti-Black sentiment” that she had ever seen. Fellow black playwright Liza Jessie Peterson followed suit, decrying Harris’ arrival on Broadway with a sweeping Facebook post that deemed Slave Play a grotesque work of art that they laugh with that laugh that’s like, ‘how could anyone say that?!’ but you thought it.

“turned black pain into ‘funny twisted camp.’” Commentators were torn, with many jumping into the fray, afraid to openly admit to liking the play’s themes around interraciality or acknowledging the playwright’s talent, while others denounced Harris altogether.

It’s easy to dismiss these concerns as nothing more than theatergoers who missed the point entirely and are now playing up and into stifling and moralistic “respectability politics” that would police black bodies and black sexual politics. But I also see something else at work. There’s an age-old idea among black folks that there are simply things we do not discuss in mixed company: that black private life and pain is ours to keep from a world that so often offers us no interiority. I can’t help but see the similarities between these critiques Harris has weathered and those that Kara Walker’s large-scale cutouts of antebellum Southern slave life endured by the black art world establishment as the artist emerged in the late ‘90s, for example. Creating popular artwork within white institutions as a black artist that centers on black trauma—work that is not necessarily delivered with quiet reverence but with a sharp poignancy and dark humor that few dare to utter but with which many agree—is always a risk, yet a necessary one.

“I can casually talk about race and sex and entanglement, and for other people it’s, ‘Skrrt, skrrt, skrrt!’,” he jokes, putting up his hands as to halt conversation. “Even if they laugh about it at a party, they laugh with that laugh that’s like, ‘How could anyone say that?!’ But you thought it.”

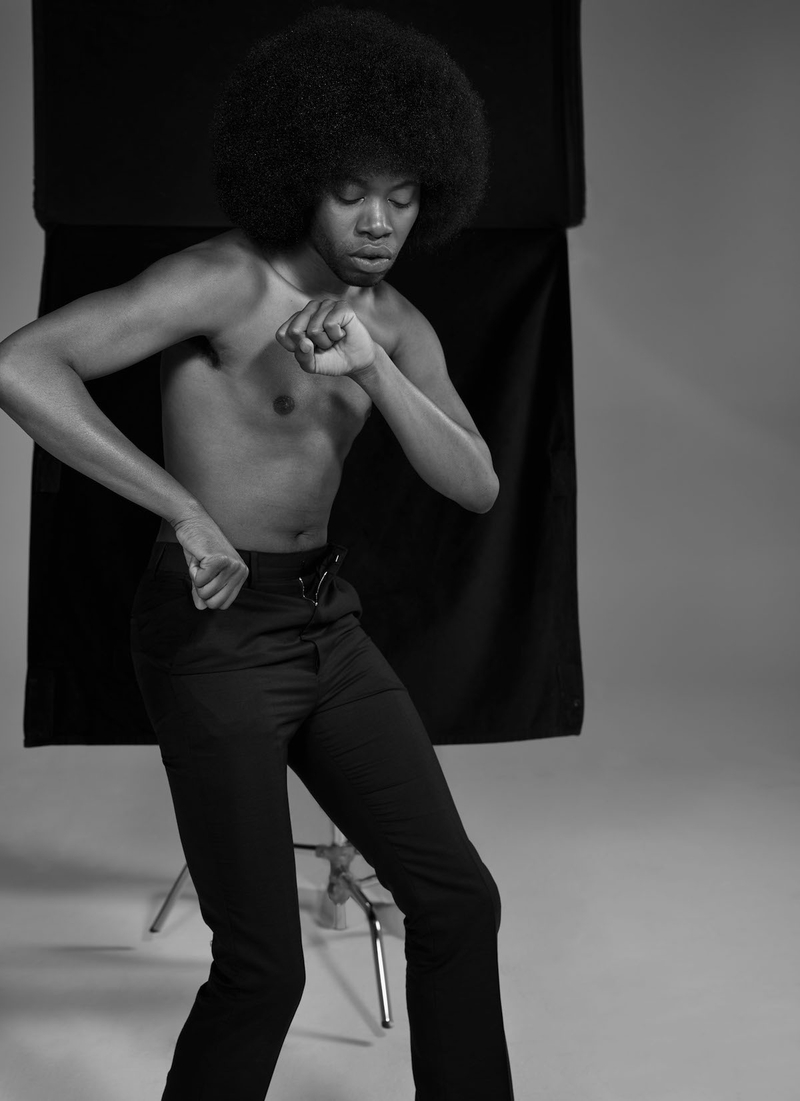

Pants: Dior Men

There is a nerve that’s missing from most public discourse today; many in the public limelight are quick to apologize or self-edit to save face, but Harris invites discourse around opposition to his work. He even recognizes the humor in people’s internal struggle with the play. “My favorite thing is when black people liked the play but want to pretend they didn’t really like it that much: ‘Here’s the thing! The play is good, but it’s not my story! I don’t really get down like that!’” he mimes. “It’s really interesting to watch people go through that. No one said that about Get Out!”

Harris only grows upset when there is no criticality applied to something he had thought very critically about. “I think what was hard was having stories written about me that are so divorced from my personhood, divorced from what I hope is an embodied generosity, divorced from the genuine joy of discursiveness,” he explains. “All these ideas about me, and also so many things that lack complexity: I will never get over the fact that there are so many people who, swear to God, are just not critical writers, talk about something I wrote critically about my psyche.” I sense a genuine hurt here.

And why shouldn’t he be? He tells me that he wrote Slave Play to give reference to the black kids who had been attending PWIs and “entangled with whiteness their entire life, including sexually, but haven’t had very much vocabulary to self-actualize as a black body inside of that and what it means to have a black body next to a white body.” Despite Harris’s natural bravado, to be critiqued, misunderstood and dismissed by your own kind is shattering. Still, in some ways it feels like a responsibility he’s willing to shoulder if it means bringing more black and brown folks to theater—or at least talking about it.

Leaning in closely and talking at neck-breaking speed, he tells me, “So the thing is, that audience gets to shift and change, and I’m doing it in a space and hoping that all the things that I’m doing will be the bridge to that shift and change. It only has to start somewhere, and I know for a fact that when I go to the box office at my play, I see more black people standing outside for it than any other play on Broadway. So that’s all I know.”

Harris is doubling down on this promise and shifting his focus to the Bushwick Starr production of his latest play, Black Exhibition, which opened in November and runs until early December. He both wrote and stars in it. Showing to 72 seats a night to an already sold-out audience, it’s an intensely personal work on what it means to be a black queer male figure who is exposed to the public. A “choreopoem” that pays homage to Gary Fisher, a gay black writer, who, after succumbing to AIDS, had his journals published posthumously by a white female teacher without his consent. The audacity and betrayal to expose Fisher rang true for Harris, who admits that Black Exhibition is about his own experience and battles as a black queer public artist unpacking their shit and vulnerability in front of thousands.

Who, then, has privilege to his narrative? What does an artist give up in sharing those struggles? Was it better for Slave Play to have stayed hidden or should it have been shared?

I can’t possibly begin to answer that for Harris, but I do know that his work has defied the odds.

When I go to the box office at my play, I see more black people standing outside for it than any other play on broadway. so that’s all I know.