On June 28, 1970, a year after the LGBT community rebelled against the New York Police Department in the infamous Stonewall riots, the city’s gay and lesbian groups walked north on Sixth Avenue together in the first march for gay pride, despite fears of violence from the police and the public. It was a sunny day, and photographer Diana Davies snapped a picture of a 19-year-old activist named Donna Gottschalk, who was proudly holding a sign that read:

I AM YOUR WORST FEAR

I AM YOUR BEST FANTASY

Gottschalk spent her early adulthood as a lesbian activist and photographer in New York, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. Recently, Davies’ photograph popped up when Gottschalk, from a rural farm in northeast Vermont, searched her name online. She reconnected through social media with a number of women who had once made an indelible impact on her life, including photographer Joan E. Biren, or JEB, one of the most noted lesbian photographers of the 1960s and ‘70s. But Gottschalk had an archive, too, which she had kept to herself for the better part of four decades.

Biren would later introduce Gottschalk’s negatives to board members of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, leading the museum to acquire a photograph for its permanent collection and exhibit it in the spring of 2017. Now, Gottschalk’s own solo exhibition, Brave, Beautiful Outlaws, is on view at the museum.

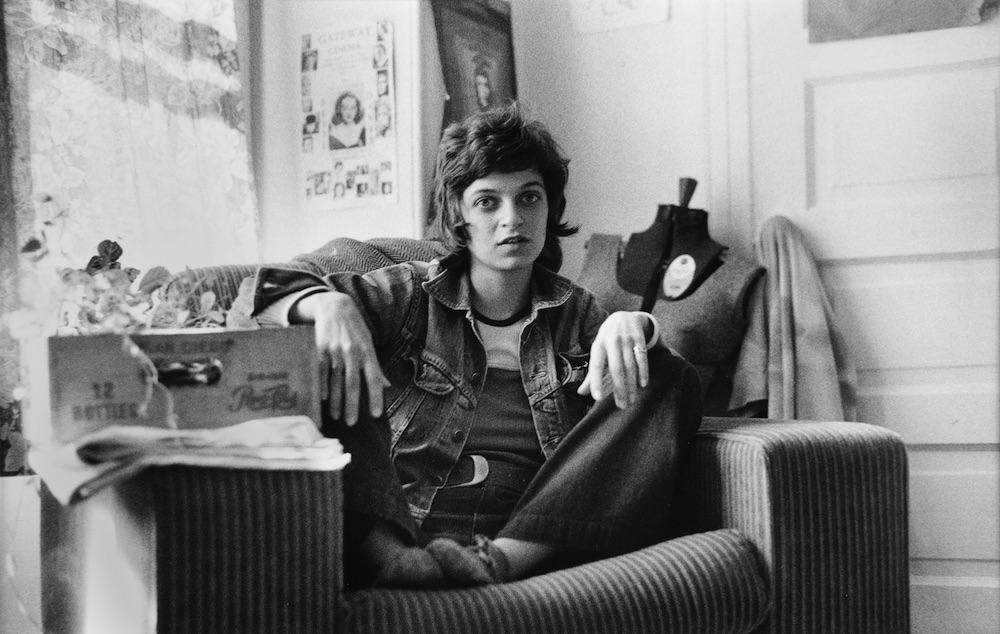

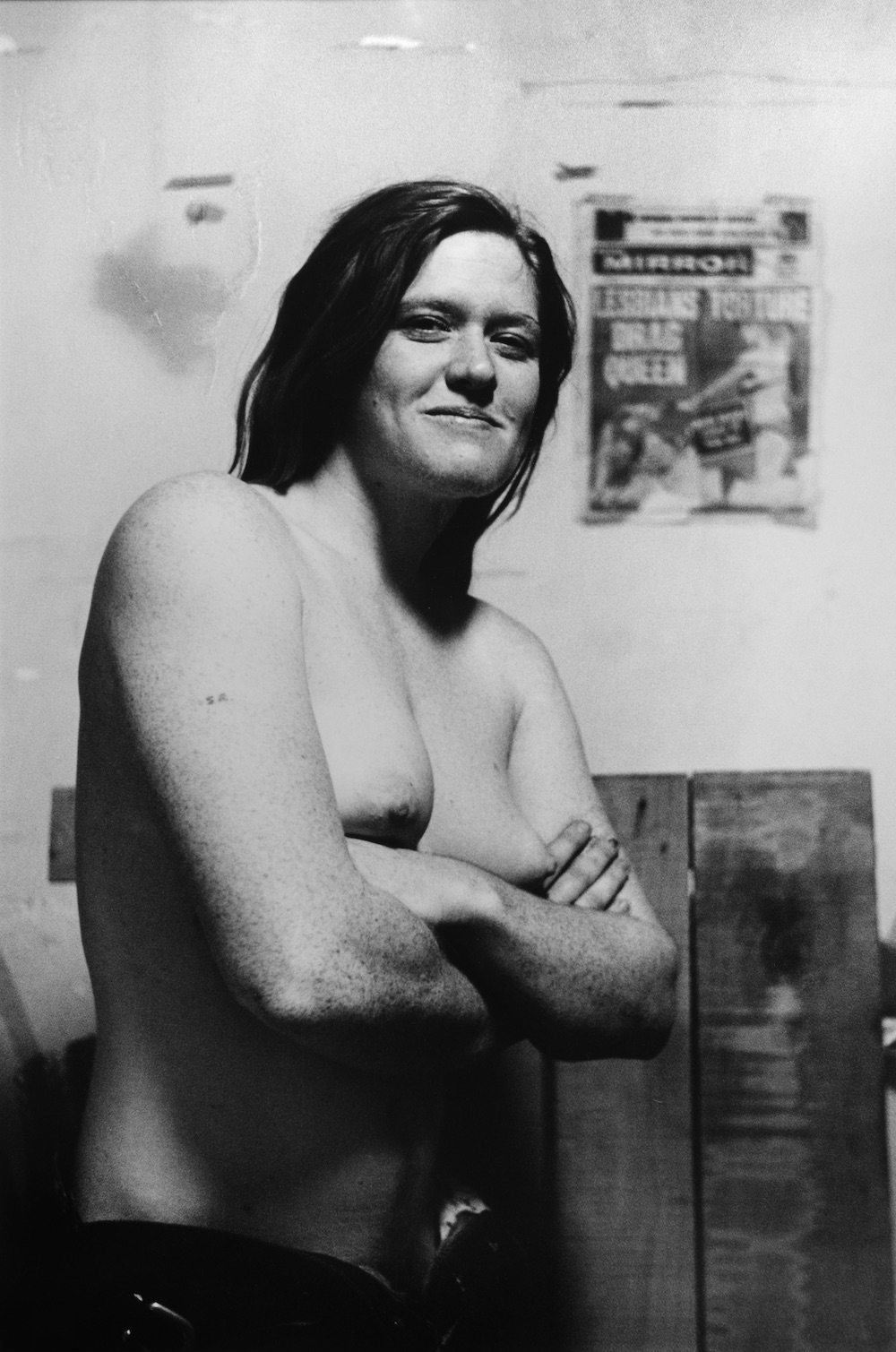

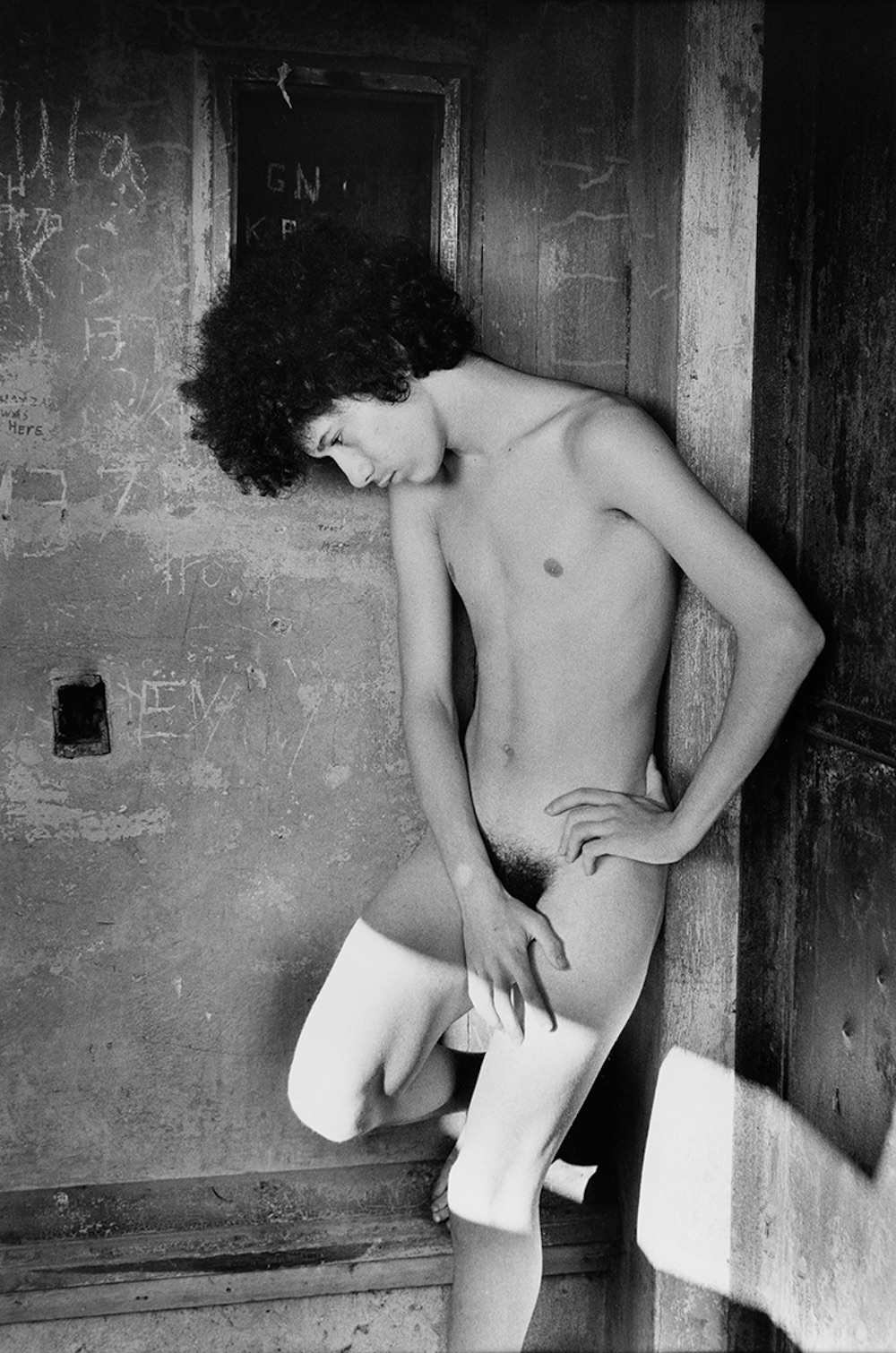

Curator and board member Deborah Bright was in awe of Gottschalk’s work when Biren showed it to her. Gottschalk had put love and care into her documentation of the years she lived in lesbian separatist communities in San Francisco. “The images were beautiful, and it was clear that they had been made with a very sensitive and engaged eye,” Bright says. “They weren’t intended to be journalistic, but deeply felt personal documents.”

“Most of the people I photographed didn’t get much sympathy in the world, and I wanted to make viewers stop and really look at them. — Donna Gottschalk”

Bright and Riya Lerner, the museum’s creative content manager, spent six months making silver-gelatin prints from Gottschalk’s negatives in the darkrooms of Brooklyn’s Pioneer Works. The scope of the project was a first for Lerner, and she says she grew close to the work. “I felt very connected to them, and I felt like they were sort of my own work, in a way, because I would spend four to eight hours a day looking at them,” Lerner explains. “These are all iconic lesbian activists who we look up to in the queer community, and being able to see them when they were young and just starting out … that was incredible.”

Gottschalk kept her negatives to herself, in short, because she didn’t intend to sell them; she only gave prints to her subjects and for the Gay Liberation Front—GLF for short. But her reasons for keeping her archive under lock and key run much deeper.

The first thing to know about Donna Gottschalk is that she is fiercely protective of those close to her. She grew up on the Lower East Side in Manhattan, in low-income tenement housing with her mother and three siblings: Mary, Alfie—who, in adulthood, would transition and take the name Myla—and Vinnie. Gottschalk often assumed a parental role. Her mother had a giving heart, she says, but she worked long hours, struggled to make ends meet, and frequently dated mafiosos. Gottschalk’s father, a merchant seaman, was a complicated man. He had an untreated mental illness and a drinking problem, and he was often physically abusive. He was not allowed in their home, but Gottschalk remained close with him, explaining, “[I] learned that the people you love can have terrible weaknesses.”

Gottschalk knew she was attracted to girls by the time she was 14 years old, but it was a man named George who introduced her to the arts scene and beatnik bars in the city and who bought her her first camera. In high school, Gottschalk began hanging out at lesbian bars, which were mafia-controlled. “I had no illusions about what my future as an out lesbian would be like,” she says. “My friends and I always lived looking over our shoulders.” She calls those years in New York as “a fucking nightmare” because of the city’s high crime rate and corruption.

Gottschalk was first introduced to GLF at age 18 when she saw an ad for it in The Village Voice. “I had witnessed how the gay bars were completely controlled by the mafia and the police, and I never fit into the middle-class, private-party scene where women would meet in their homes to drink, dish, and sleep with each other but stay tightly closeted in straight company,” she told Bright. By contrast, GLF was taking action and fighting for a cause.

In the early days of GLF, the number of queer women were few, and the men often dominated the conversation. The women began meeting separately and, as their numbers grew, they planned protests and established new social events, such as dances, to give queer women somewhere to socialize outside of the bars—risking blowback from the mafia for taking away their business.

Gottschalk began to notice which members had aspirations for fame or power, and by 1970, when Biren started galvanizing the women to move to D.C. to be closer to the White House, Gottschalk wanted to actively avoid political drama. “I only wanted to take photographs, for the most part,” she says. She did follow Biren to D.C., however—they had history, and Gottschalk found her irresistible—and she took a job in a print shop while photographing for radical feminist publications. The shop owner eventually became her lover, and together they drove out to San Francisco in 1971 to get away from the political infighting and begin a new life.

San Francisco was eye-opening for Gottschalk. “Every other person on the street was gay, so that was a tremendous relief,” she says. The lesbian bars were run by women and, she adds, “the city itself was teeming with women from all over the country.” Gottschalk rented a three-bedroom apartment in the Mission District and reached out to her siblings to join her. Myla, who at 15 years old was still known as Alfie, and Mary, who was 21, arrived first, and both came out as gay. Vinnie, 12, followed, but he could not read or dress himself due to what Gottschalk believed was neglect. She spent six months teaching him to read by buying him comic books, and he became more self-sufficient under her care.

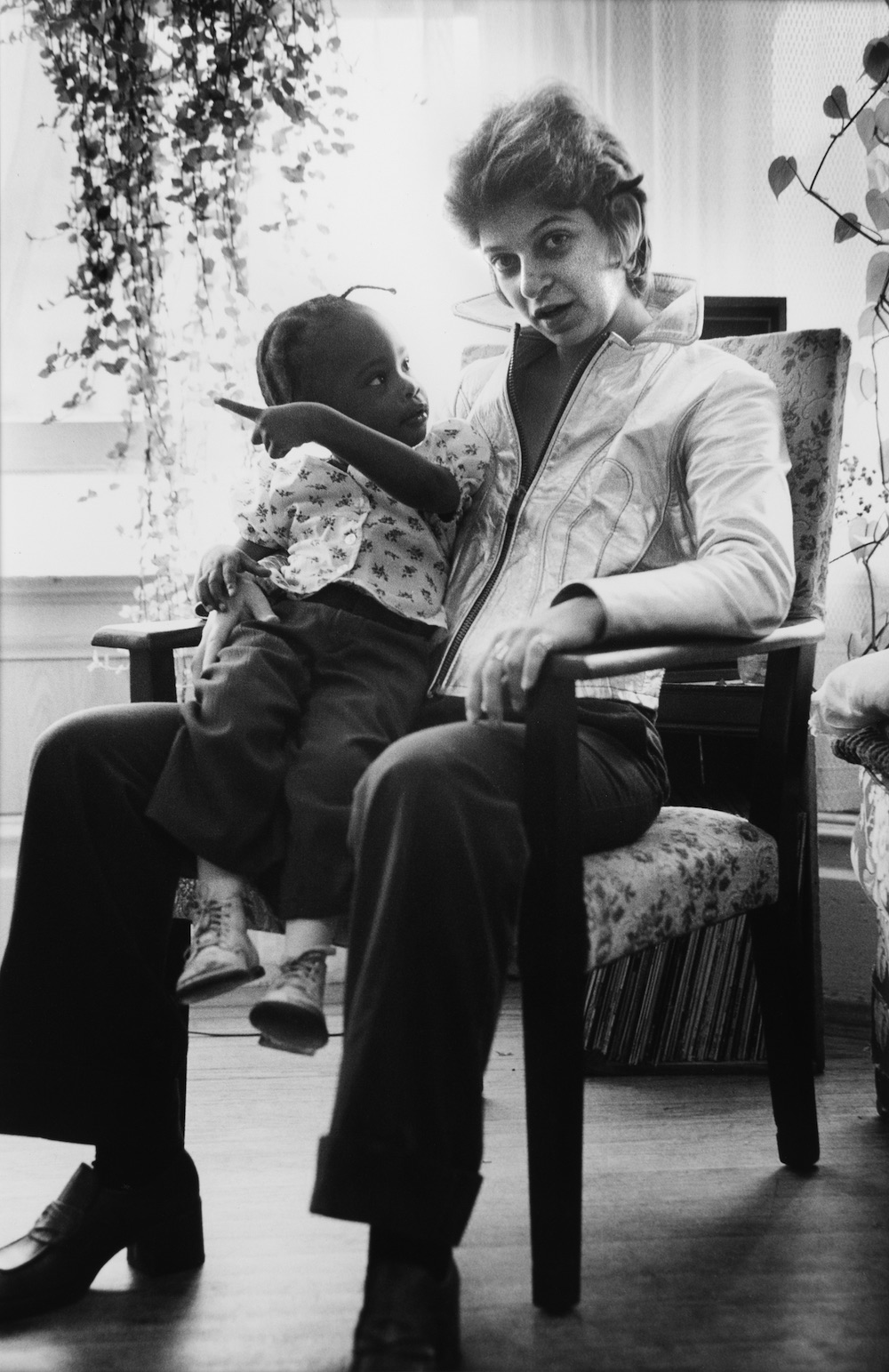

“Occasionally we put up gay radical women visitors from the East Coast in our apartment,” Gottschalk recalls. “Sue Katz was one of these women and the whole family hit it off with [her]. She also became one of my most photographed subjects.” Gottschalk drove a taxi using a fake license to make ends meet and joined an activist group founded by Katz.

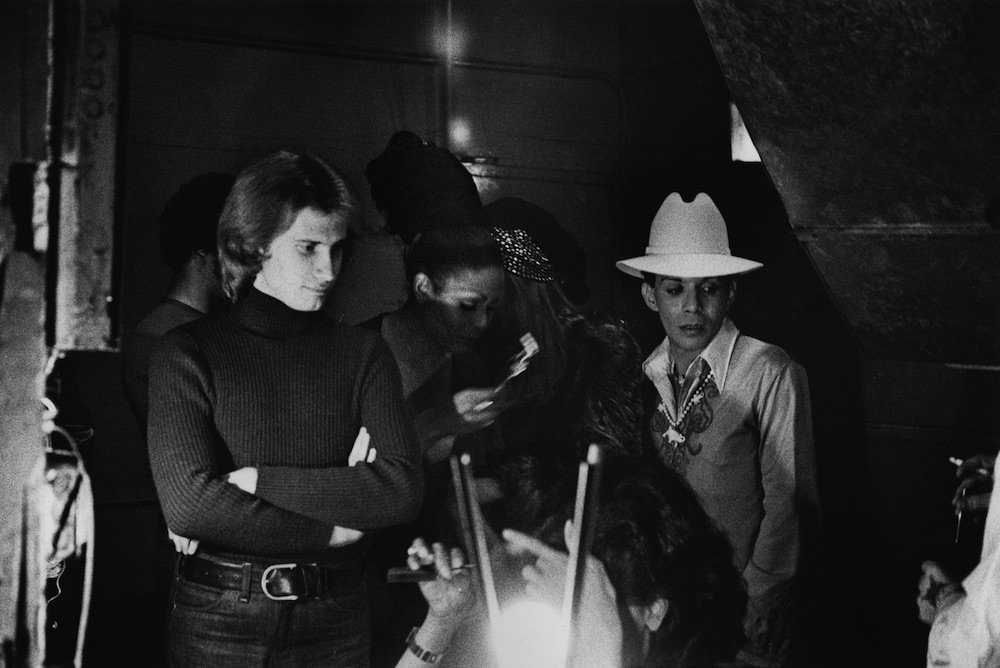

Gottschalk’s photography during this period was informal, almost snapshot-like, documenting her friends and lovers. But the aspects of her images that make the work feel so contemporary today didn’t draw positive feedback from her subjects at the time. “One of my lovers, I took her picture and she goes, ‘But I look so tired, I just look so haggard,’ and I said, ‘Well, you are,'” she recalls with a laugh. “They weren’t used to having anyone who wanted to take their picture, and they weren’t used to what they saw, I guess.”

Sue Katz, for example, was known for her radical, controversial opinions, Gottschalk says: “She was an absolute political firebrand.” But in an early photograph of a 25-year-old Katz, she looks to be barely a teenager. “What was so shocking was that, in truth,” Gottschalk says, “she was a tiny, frail girl.”

But despite having found a real home in San Francisco, Gottschalk started observing cracks on the surface. At 18, Myla wanted to undergo gender reassignment surgery. Gottschalk said no—at the time, there was no government support for trans people. The costs were prohibitive, and she knew Myla would have to turn to prostitution to pay for it. Gottschalk already suspected she had begun stepping into that world, and she didn’t want that life for her. Myla didn’t broach the subject of surgery again until late adulthood. “For thirty years,” Gottschalk says, Myla was “never really happy.”

Mary and Myla both developed drug addictions, and around 1974, Gottschalk lost the lease to her apartment. She was burnt out from life in San Francisco, so she took Vinnie and drove back to New York City. It wasn’t any better there, which led Gottschalk to eventually take refuge in Connecticut, where she opened a photo lab with her partner, Tony. They ran it for 38 years before moving together to their farm in Vermont. Today, Gottschalk works in nursing homes; after Tony became ill and required round-the-clock care, she became a caretaker at home, too.

Tragedy has made its mark on Gottschalk’s life. Her sister Mary was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and died from medical complications in 1993, while HIV and drugs took a heavy toll on Myla and she died, too, in 2013. Many of the women close to Gottschalk in her youth also met early deaths, and with each passing, she became more and more protective of her negatives. She didn’t share her work earlier when it was still dangerous to be an out lesbian; later, it became too painful to revisit her memories, and she didn’t want to hear any criticism of her photographs.

After Biren showed the negatives to the Leslie-Lohman Museum, an institution that would not have been able to exist when Gottschalk was photographing, Gottschalk agreed to let her work be seen. “Most of the people I photographed didn’t get much sympathy in the world, and I wanted to make viewers stop and really look at them,” she says. The exhibition will also includes a body of work on Myla from age 11 up until a few months before her death. Of those, Gottschalk says, “I need the pictures to show, to explain, because I can’t explain [it].”

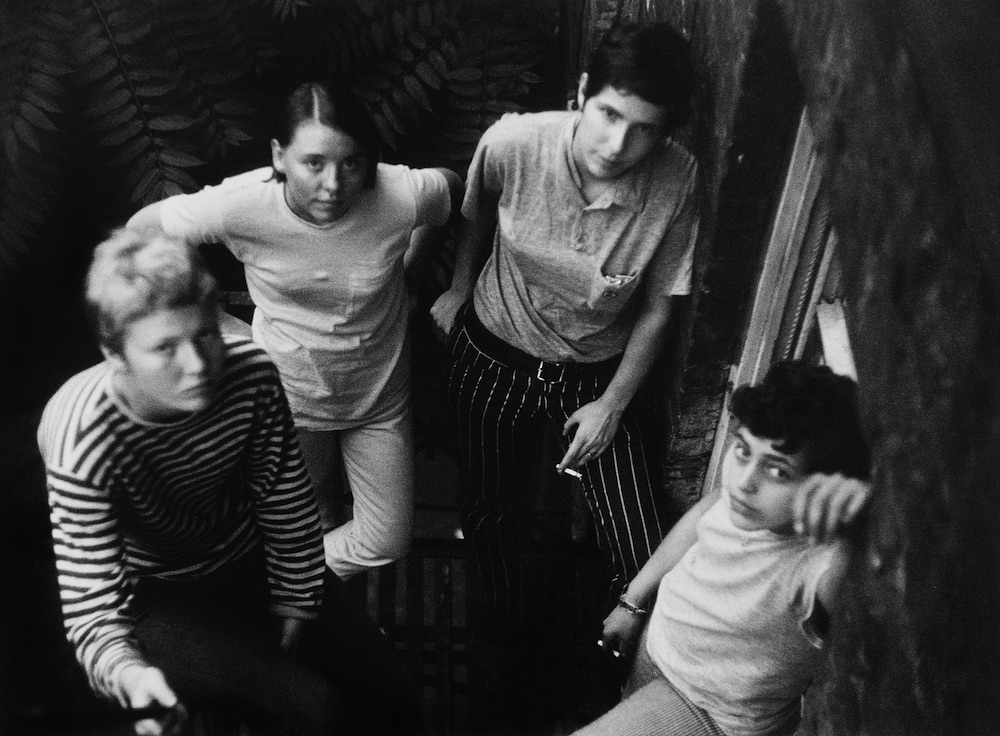

Robin Chaia Mide, 1968, Donna and friends on the fire escape, E. 9th St., silver gelatin print/ 2017, 20 x 16 in. Collection of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art.

Gottschalk’s photographs add an underrepresented voice to photography, because while there were plenty of images of gay men at the time, there were relatively few of lesbian women.

“I think that her work is really important and significant in that way,” Lerner says. “It shows this world that didn’t get a lot of representation.” Equally, her portraits of Myla, and of other trans people, Lerner says, remind people that “queerness is not a new phenomenon.”

Despite the strides that have been made toward inclusiveness of queer voices in contemporary art, there’s still work to be done. In the art world, Lerner says, that means “[to not be] pigeonholed as like, ‘Oh, this is queer work,’ but just, ‘These are photographs.'”

For Bright, the pointedness of Gottschalk’s decades-old work can be found in the current political atmosphere, “how bigotry and prejudice are always under the surface and can rear their heads when political winds change,” she says. “There are still many parts of the country where LGBTQ people are stigmatized, bullied, and intimidated into closeted silence.”

That tenacious spirit lives in Gottschalk’s photographs of her queer community. As she told Bright: “They were brave and defiant warriors who insisted on being, whatever the consequences.”