When she makes music, Kelela Mizanekristos is constantly looking for the “OG version”—the original version of a song intended to have many variations. From the very beginning of her career, Kelela—who goes by her first name professionally—was made to be remixed. Coming from an underground club music culture, her sound is malleable, equal parts dance and R&B, an organic heart with digital armor. It’s rooted in the dance floor but often smolders in the bedroom, with each subsequent re-edit a conversation with past and future versions of itself.

“I’m someone who comes from remix culture and loving edits, and loving the thing of making and remaking, and hearing it repurposed and reimagined,” she says. “You get sort of lost in ‘What is the one, though?'”

In the process of making her debut EP Hallucinogen, she made several versions of every song on the record, following herself down the rabbit hole, exploring different tangents, trying on and feeling out each one, looking for the “OG” version. It’s a search that’s defined her whole career. And while she appears to have found herself, Kelela is still searching.

The child of Ethiopian immigrants, Kelela grew up in the Maryland suburb of Gaithersburg, about 20 miles north of Washington, D.C. She was exposed to all kinds of music growing up—Miriam Makeba and Harry Belafonte from her dad, Green Day from the white boys in school, The Sound of Music VHS tapes, Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814, and Björk’s sonic evolution.

Kelela missed out on taking the conservatory track to a music career—while she nailed her audition for the Duke Ellington School of the Arts, she couldn’t afford the out-of-District tuition. Still, she trained in classical violin until the twelfth grade and sang in jazz bars in her teens. She stayed local for college, studying first at Montgomery College in Rockville before transferring to the School of International Service at the American University in D.C. She’d moonlight at open mics at the Eighteenth Street Lounge, and later, she covered jazz standards during open mics at HR-57 and Cafe Nema. She joined an indie band called Dizzy Spells and dabbled in the prog-metal scene after meeting Animals as Leaders guitarist Tosin Abasi.

But she had also been failing in school, completely distracted by the music career she hadn’t fully committed to. A semester away from graduating, she dropped out. By the fall of 2010, she’d packed up and moved to L.A.

It was there that Kelela would connect with Fade to Mind and Night Slugs—sister labels with a roster of producers on the bleeding edge of underground club music—and drop the 2013 mixtrape Cut 4 Me that would kick off her career in earnest at 30 years old. It took a while for her to find her tribe, but when she did, it just felt right. “It was a very inspired sweep of things that happened one after the other,” she explains.

Up until that point, most of Kelela’s musical endeavors felt like experiments, waypoints along the journey to her true self. One of those experiments, a demo she cut with a friend, got passed until it landed with Nick Weiss and Logan Takahashi of the alt-electro duo Teengirl Fantasy. The track they’d make together, “EFX,” would offer a glimpse of her adeptness at lacing glitchy, skittering electronic productions with analog warmth. Ultimately, it was Ashland Mines, a DJ and producer who performs under the name Total Freedom, who would connect her to the Fade to Mind camp and plant the seed that would become Cut 4 Me.

Before they connected with Kelela, Fade to Mind and Night Slugs—comprising the DJs and producers Kingdom, Nguzunguzu, Bok Bok, Girl Unit, and Jam City—didn’t really work with vocalists, occupying underground clubs in L.A. (Fade to Mind) and London (Night Slugs) with some of the most forward-thinking dance music of their generation. But there was still a cold, sharp edge to their compositions, alien transmissions in need of a human touch. In this way, collaborating with Kelela was a godsend; a singular voice imbued with cybernetic soul, she toed the line between the organic and the electronic, the perfect voice to bring the underground labels into a pop space. Kingdom’s “Bank Head” would prove to be their breakout, a master class in rhythm with syncopated, machined drums and Kelela’s coos swirling around a steady 4/4 clap. At the time of its release, Kingdom told Dazed, “It has the right balance of club sounds and sex appeal…. It’s brought the track to people that don’t follow experimental club music or Fade To Mind.”

As an artistic statement, Cut 4 Me is distinct. It served as a showcase for the producers, sure, but also for the infinite varieties of Kelela—it’s her touch that pulls these club rats out from the underground and into the light. But she always intended for the mixtape to be somewhat of an amuse-bouche, a little taste of what she had to offer before serving up the main course. Even while she was making Cut 4 Me, she had songs that she held back that would ultimately end up on Take Me Apart, her debut studio album released last year.

She says, “It’s a mixtape because I chose not to go H.A.M.” (Hard As a Motherfucker). “I was like, first idea best idea, hit it and quit it, get it and get out. Show the idea … that’s what I was trying to do. Look at this and how they sound so cool together. Don’t they sound cool? And then, I’ll be right back.”

The next step would prove tougher. In the aftermath of Cut 4 Me, she fielded major label offers but balked at their 360º deals—contracts where the label takes a cut of all of an artist’s revenue, not just the recordings—and ultimately signed with the indie-electronic label Warp, home to the likes of Aphex Twin, Flying Lotus, Oneohtrix Point Never, and Danny Brown. “What I didn’t want to experience was negotiating my artistic life with a label,” she says. “Just the value that they place on the things … that support really matters. And that they’re not asking me to give them all of my money. That also matters.”

Hallucinogen was marked by growing pains—ultimately released on October 9, 2015, the date had been pushed back several times to accommodate her obsessive production habits. But with more life experience came growth, and as she evolved as an artist, her perspective shifted. “Over time, the more experiences that I have, the more I know who I am, the less I’m taking people’s bullshit,” she says. “I had to do a lot of experimenting with a lot of different people to try to figure out what it is that I’m trying to say, to get to something that now I’m clear about. I’ll never really make an album like that ever again, because I’ve now pretty much explored every way.”

Throughout all of her musical life, with each experiment, Kelela has always searched for the intersections between the different lanes she’s explored. When she set out to make Hallucinogen, her first album for Warp and her first attempt at building a record from the ground up, she looked to build off of those intersections. She still had the club banger, the irresistible dance floor bop that is “Rewind,” but also the slow-burn Rap&B vibes of “All The Way Down” and the acid-dripped “Gomenesai.”

She branched out from her Fade to Mind/Night Slugs family, working with the hip-hop producer DJ Dahi—best known for collaborations with Drake (“Worst Behavior”) and Kendrick Lamar (“Money Trees”)—and Venezuelan experimental noise producer Alejandro Ghersi, a.k.a. Arca. Arca’s solo work is intensely atmospheric, rich in texture and uninhibited in form. His collaborations with vocalists FKA Twigs and Björk tend to find the sweet spot between rhythm and blues and complete aural chaos. By comparing his solo work with that which he makes with Kelela’s peers, one can begin to see just how different her style is from these women to which her work is often compared.

Arca’s sessions with Kelela are defined by movement. “We make dance music together,” she explains, “so even when it’s a ballad … even ‘A Message,’ there’s just really clear movement that’s happening. I like to be really animated, I’m standing up, dancing, trying to identify the groove. But Alejandro is also like that, so we really set each other off when we’re in the room together. There’s a lot pacing, a lot of catwalk.”

Hallucinogen feels like a self-contained narrative, a short story painted with the various colors Kelela was working with at that moment, but Take Me Apart feels like the record she spent her whole life making. Its trajectory began back before the Cut 4 Me tape dropped, with sketches that felt too ambitious for a mixtape, or that just needed some room to breathe.

As she put together the album, she sought out the various intersections of all of the production she loved, finding where they fit together. If she starts with an Arca track, all woozy and draped in crunchy textures, but then she wants to drop some cello on top and slide some Jam City machine claps in there, she’s looking for the places that fall in between all of that next. “I could break it down to particular sounds, too,” she offers. “It’s pretty literal for me. I love the low end on this. I wanna combine that low end with the mids-y parts in this. It’s gotta be this type of pad from that thing.”

“I have to do the thing that would make me feel the most uncomfortable, the thing that’s most hard for me, because then you get an image that feels more urgent.”

As she went down that rabbit hole, constructing custom puzzle pieces to fit together all her disparate references, the result is an album of densely layered songs that reveal subtle nuance with each listen. Her tightrope walk between the pop grooves and experimental sound design feels effortless, even if the truth is far from it. She follows just enough structure to keep you from getting lost in the noise, but veers far enough to always keep it interesting.

Take Me Apart’s opening track, “Frontline,” is about as straightforward R&B as she gets, but it still incorporates intricate drum programming and a vocal performance with an incredible sense of rhythm and melody, channeling Aaliyah and Janet Jackson’s masterful intonation and breath control. The record’s sequencing is inspired, riding waves of energy through peaks (such as the post-club tryst that is “LMK”) and valleys (like the gentle bubbling brook hiding in the mix on “Jupiter”), taking us on a guided journey through the places she’s exploring.

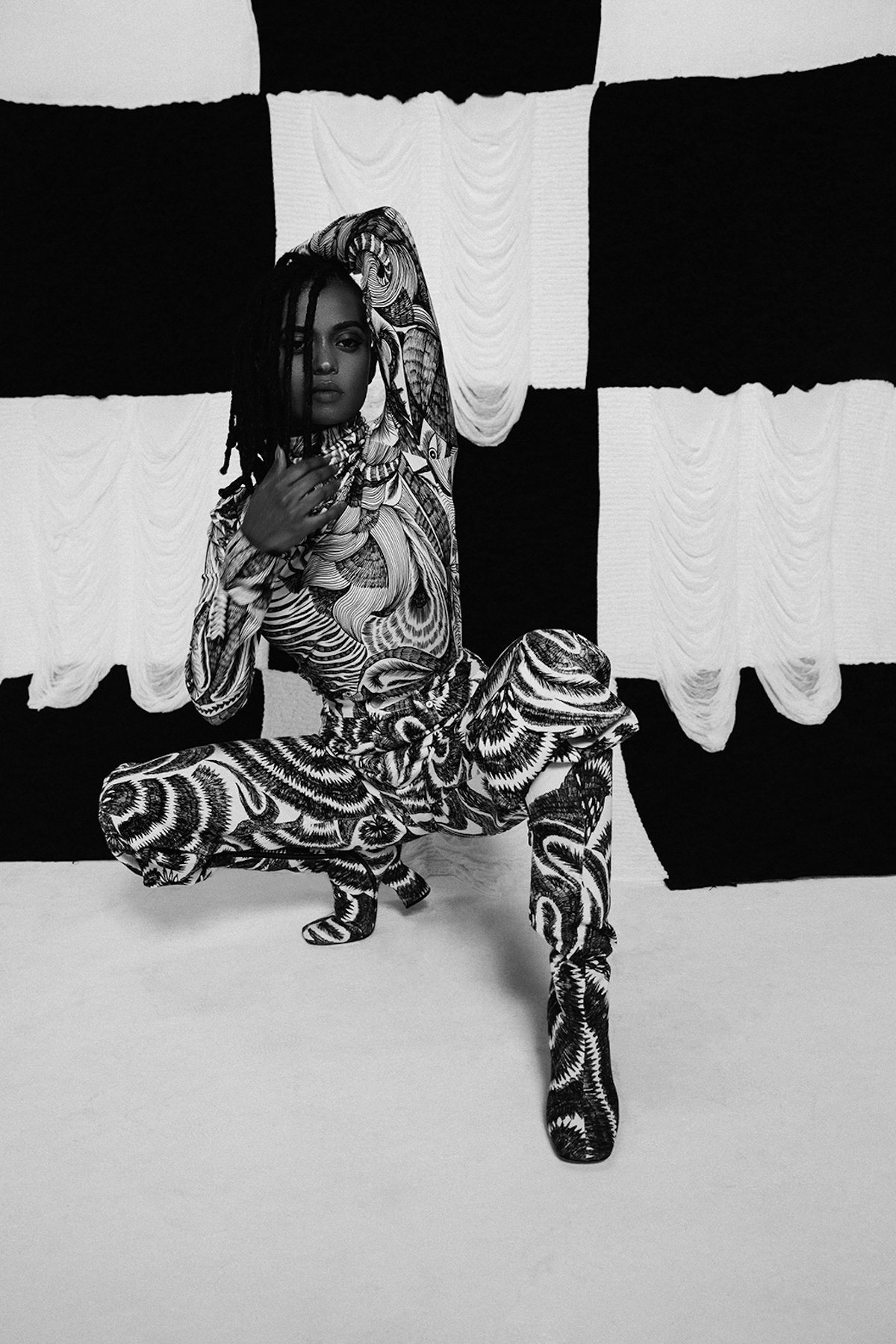

With her musical identity fleshed out and the language she uses to create music refined, Kelela has given increased focus to honing her visual communication. She works closely with her creative director, Mischa Notcutt, editing references and creating mood boards, whether for magazine features like this one or the album cover for Take Me Apart.

“People who have gone to fashion or art school, there’s just a way that they can talk about images that’s been inspiring for me to experience, but that I also just don’t have a stranglehold on,” she says. “With music, I feel like I have that language and I know exactly what it is that I’m saying. But with visuals, I’m trying to name what it isn’t, and then, in a feeling-it-out type way, naming what it is. I’m carving it out.”

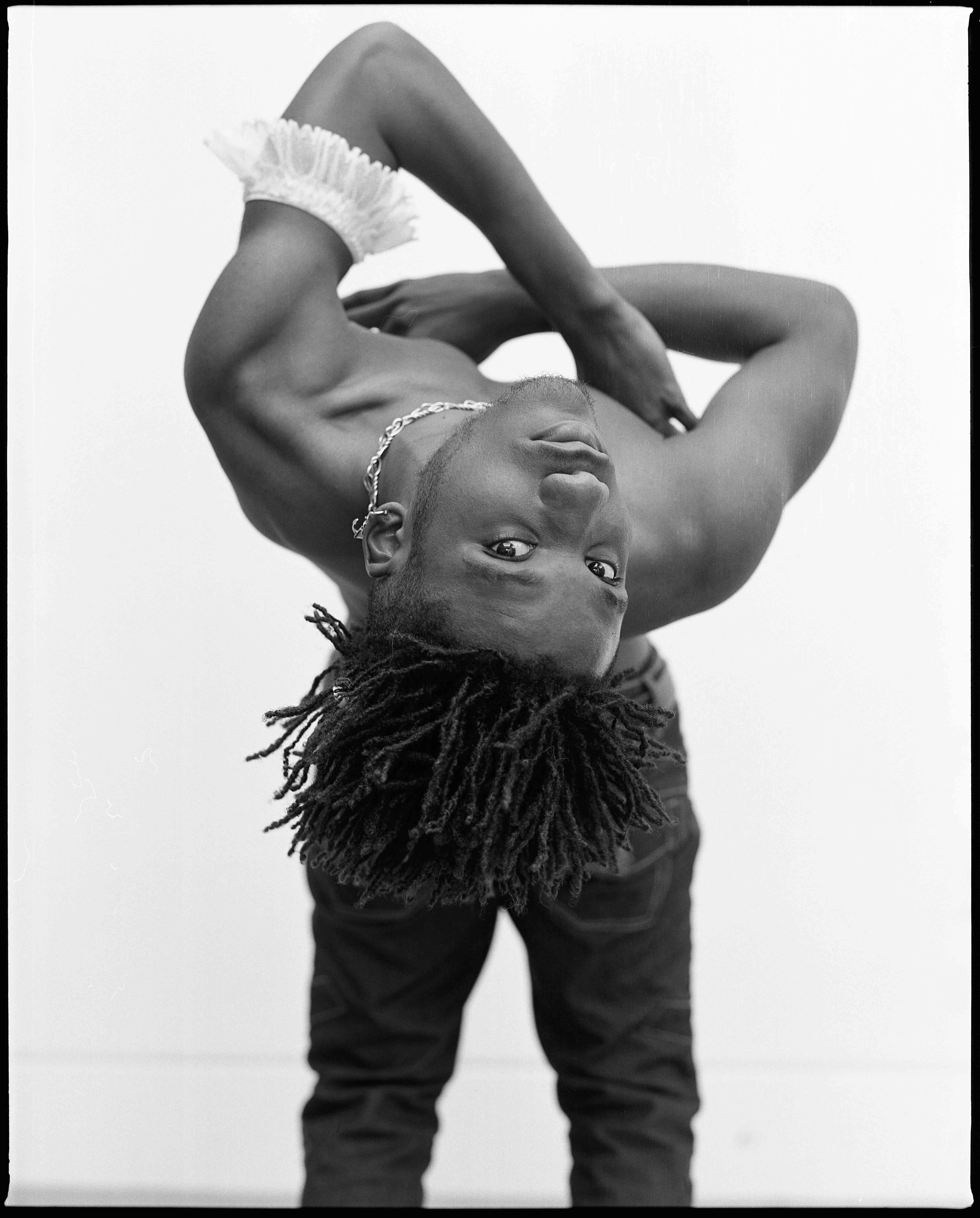

The art for Take Me Apart, shot by German photographer Daniel Sannwald, illustrates the sort of alien intimacy that defines her music, juxtaposing a nude portrait that says, “I’m your friend, I have a body just like you do,” with the 6-foot-long dreadlocks that scream, “I’m not your friend, I’m not even of this world.” It’s a construct, but it feels real, simultaneously projecting strength and vulnerability. “I have to do the thing that would make me feel the most uncomfortable, the thing that’s most hard for me, because then you get an image that feels more urgent,” she says.

And much like she gets to reinvent herself with every photo shoot and everything she’s styled in, Kelela writes her songs with the expectation that they will be remixed, re-edited, and reimagined after they’re released. She may have a firm grasp on the “OG version,” but that only serves as the benchmark. It’s part of the underground club culture’s ongoing conversation between artists across generations. Both Cut 4 Me and Hallucinogen got full-length remix treatments, and she’s currently in the process of executive-producing the remix counterpart to Take Me Apart, which will comprise almost all new collaborations. As she recorded her vocals, Kelela was mindful of future remixers, separating parts and stemming out individual tracks to give them the most freedom possible when reworking her music. And the conversation goes both ways; any producer that agrees to participate must also send back their own stems for her to re-edit. She works with a lot of producers that are also DJs, and DJs make music for the club—pop song structures need not apply. But Kelela has such a strong feeling about where that form should fall, in between the club and the radio, and when to showcase the vocal or when to showcase the instrumental.

“Especially in electronic music, the people who are canonized while they’re alive are white, for the most part, and the brown people who are canonized, it’s when they died or when it’s just already happened. After the white guy samples the thing, then that guy gets a revitalization sort of thing for his career. And I’m just like … let’s not do that.”

“It’s gotta go through this filter,” she says. “We’re not trying to adulterate the thing, but there is a way that I’m always like, this part goes too long, we gotta do this … there’s a lot of things that are sort of passed over, like, oh no, that part is the part, that part needs to happen over and over and over … that’s sort of how I’ve wanted to approach it. They’ve all been so incredible, they’ve just submitted so much heat.”

But the remix goes beyond just a musical convention for her. It’s part of her manifesto, part of how she sees what she does, her attempt to rewrite the canon. It’s a way for her to provide a platform for the people in the artistic community she comes from, directing eyeballs on those who are helping it thrive and continue. The club is where people go to have fun, sure, but it’s also a safe haven for society’s outcasts; the place on the fringe where the marginalized can be heard, where they’re free to be themselves.

Almost every song on Take Me Apart has been remixed—some several times—each one pointing to a different creator, from different scenes all over the world. The versions that don’t make the final cut will be reworked into a mix by Nguzunguzu’s Asma Maroof, optimized for the club, the music’s natural setting, and an important symbol for the people who inhabit it.

“It’s quite literally a place where a lot of people find refuge who would otherwise not find refuge in the world. So on a political level, there’s something that’s really important to me,” she says. A big part of her mission is including people in the canon who are typically excluded until their moment has passed, or ignored until someone within the establishment anoints them, declaring them now relevant. Kelela’s doing her part in writing a new, inclusive canon, and supporting great art whether the artist is 22 or 42, from Africa or Atlanta.

“For me, this record, the remix project, part of my intention is to canonize people while they’re living, while they’re doing the thing that they’re doing,” Kelela says. “Especially in electronic music, the people who are canonized while they’re alive are white, for the most part, and the brown people who are canonized, it’s when they died or when it’s just already happened. After the white guy samples the thing, then that guy gets a revitalization sort of thing for his career. And I’m just like … let’s not do that.”

“You should know that these people exist right now, and that they’re killing it right now. And also, listen to how cool it is. Did you know that that’s happening?”

Photo Assistant Owen Smith-Clark

Styling Assistant Jennifer De La Cruz

Makeup by Raisa Flowers

Nails: Madeline Poole

Set Design: Kristian Kirk

Produced by Nicole Van Straatum

Special thanks to Dune Studios.