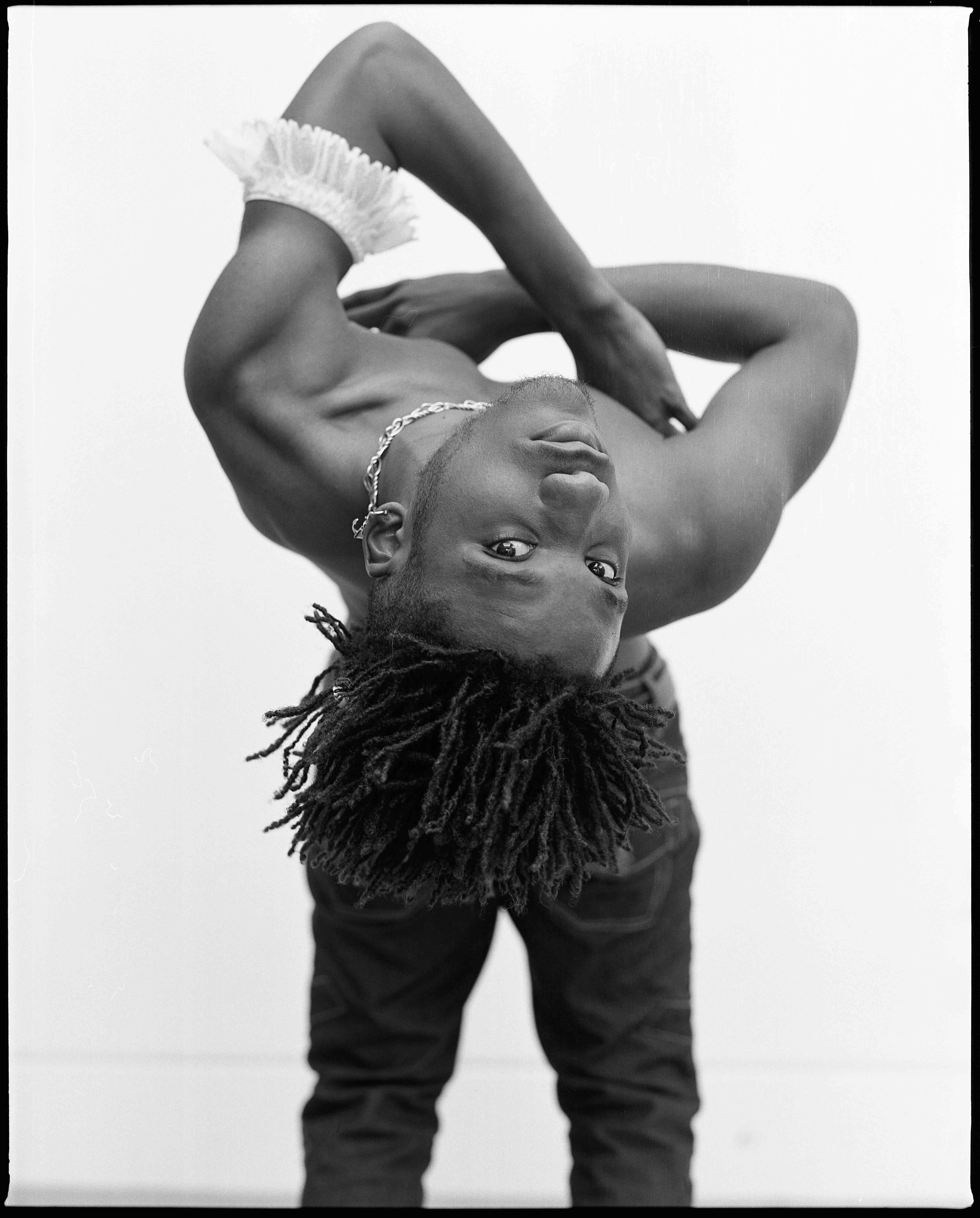

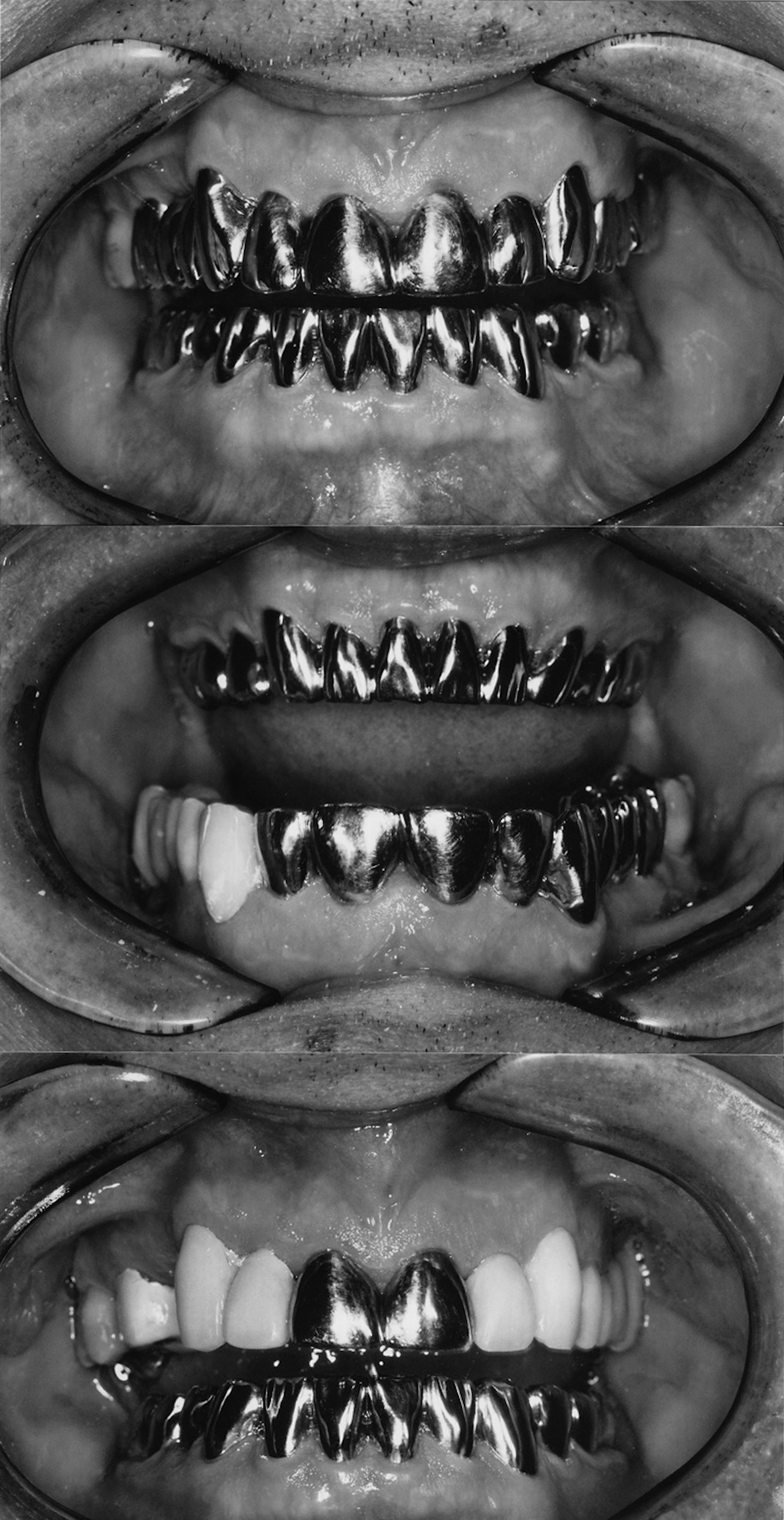

Artwork by Genesis Breyer P-Orridge

While interviewing the legendary multidisciplinary artist Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, all I could think about was a small installation by Louise Lawler at her retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Beside a picture of Andy Warhol’s Round Marilyn (1962) is a small Plexiglas placard with gold lettering that reads “DOES ANDY WARHOL MAKE YOU CRY?” I could only bear to stand in front of it briefly, because of course the answer is a resounding “YES.” It’s not that I have any fondness for Warhol. Rather, I began to think about the precariousness of queer lives, legacies, and attachments. It is the kind of sadness that makes you remember things that may not have even happened, things that you thought you wanted that never materialized.

P-Orridge, unlike Warhol, has no interest in legacies, even though s/he has certainly created a singular one. [P-Orridge uses the pronoun s/he and speaks in the first person with the collective “we” as an ode to h/er ongoing collaborative Pandrogeny Project with h/er partner, the late Lady Jaye.]

“Legacies are a complete waste of time,” s/he says with a chuckle. “For a start, we are not going to be there to enjoy any legacy if there was one. So why bother? And legacies can change according to what the overriding culture becomes. Legacies are just another distraction that trick people into trying to measure themselves against something so abstract.”

P-Orridge may not call it a legacy, but s/he has made massive contributions to art and activism—the following list of which is nowhere near exhaustive. S/he was a founding member of COUM (Cosmic Organicism of the Universal Molecular) Transmissions, a music and performance art collective active in the United Kingdom from 1969 until 1976. COUM’s 1976 Prostitution Show at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London was an early target of art censorship by the far right; the use of used tampons, erotica, and transvestite guards ignited panic in the British Parliament. S/he would later front the industrial band Throbbing Gristle, and then the experimental video art and music group Psychic TV.

After years of government suppression and harassment of h/er anti-establishment artistic activities, P-Orridge moved to New York, where s/he met Lady Jaye, who became h/er wife, partner, and collaborator. Despite Lady Jaye’s death in 2007, the two continue to collaborate on their Pandrogeny Project, P-Orridge says, a lifelong process of radically becoming as one, physically and spiritually, through body modification and interdimensional psychic communication. The ongoing exploration even caught the attention of Marc Jacobs, who invited P-Orridge to star in his 2016 Spring/Summer campaign—though s/he did not get to keep the outfit. Perhaps most revolutionary is this use of h/er own body as an activist and aesthetic tool, an idea s/he has embraced from the very beginning. As s/he suggests, “Using ourselves means ‘the artist is always present’ in the artwork. That’s intimate.”

“Every single second in life is an added bonus that we might not have ever had. Knowing that led me to open up my mind to any and every vision or opportunity that would benefit humanity in some way.”

It was exactly this intimacy that moved me to tears—not once, but twice. The first time was after a panel I was on with P-Orridge at Invisible-Exports gallery in New York. I remember walking back home with my roommate over the Williamsburg Bridge after the event and feeling that something incredibly transformative had taken place. The second was after talking to P-Orridge for this feature, just after I had relocated from New York to Los Angeles. The boy I was in love with did not ask me to stay, and I was—and remain—heartbroken. I asked P-Orridge about unrequited love, to which s/he replied, “We always assumed we were somehow to blame. We always think it is a flaw in what we have done or said or been, that somehow we failed to tell someone accurately. My only response is to always give more love, to be even more generous with what we have, hoping that by example it will reflect back and cause a short circuit in the other person so that they have a moment of realization. You can’t make love happen.” This might be a more useful way to think of a legacy—a way of life that constantly drives one to give more—even in the face of rejection—and to live flamboyantly in the most devastating circumstances.

It had been quite some time since I felt so fully understood by another person, and I wondered if P-Orridge had ever felt lonely, or if s/he ever felt completely by h/erself in an idea or experience. S/he responded with h/er characteristically collaborative spirit: “It’s more about having revelations where you realize you have this massive task ahead of you, where you have to communicate what you feel you’re seeing. Every single second in life is an added bonus that we might not have ever had. Knowing that led me to open up my mind to any and every vision or opportunity that would benefit humanity in some way. That’s what art is—how do we give back enough visions and ideas and alternatives so that we don’t just survive, but we thrive?”

“The collective has been dismissed by people in power because of the threat that it creates. It terrifies them as a model. The collective is a threat to the individualistically built alternative that we live in. Alternatives are dangerous to the status quo.”

It is clear that P-Orridge is not just someone who talks big—this sentiment has always been the ethos of h/er work. S/he suggests, after I wonder if there is a finite amount of one’s self to give, that “you can keep some emotion for yourself, but when you do it with everyone else, there’s still plenty. It has to be collective. The collective has been dismissed by people in power because of the threat that it creates. It terrifies them as a model. The collective is a threat to the individualistically built alternative that we live in. Alternatives are dangerous to the status quo.”

Moreover, this engagement does not end when the going gets tough. I began to tear up when P-Orridge explored the roots of h/er endless strength in response to government censorship. “That’s the job,” s/he says. “You cannot back down, no matter what. You can’t back down. The only way to get through that kind of attack is to be surrounded by an extended chosen family of people who truly love each other enough to sacrifice for each other. These are qualities that have so much value—chivalry, loyalty, devotion, unconditional love, and generosity.”

My mind shifts from Louise Lawler to a Dean Wareham lyric: They said it’s wrong to live so fast and feel so strong, but why can’t I have mine? P-Orridge has lived with unrivaled vigor and loved with the depth of an ocean, and perhaps I cried because I feel I haven’t. But there’s always time to remedy these tears—at least until there isn’t.

All images courtesy of Invisible-Exports, New York.